Importance of Vegan Seasonal Food

As the air begins to chill and the scarves and sweaters come out of storage, autumn sets the tone for a shift in fashion, foods, and recipes. Nothing screams fall like a good gourd, a warm soup, or the classic pumpkin-spice flavored anything. But among the traditions is an unexpected benefit of eating vegan seasonal food: it’s a positive impact on the environment and the body.

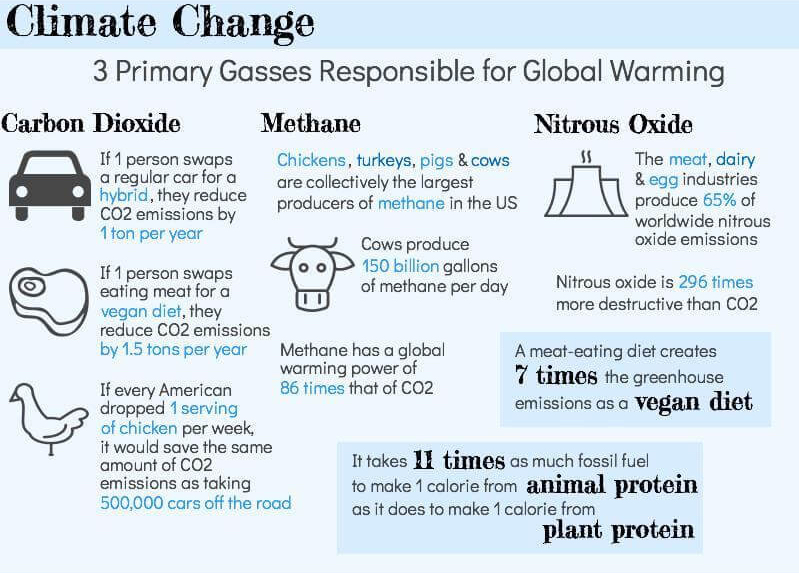

The quest to save the planet is never-ending and filled with large and small-scale issues the population contributes to and fights to improve. But as the leaves change, it presents an opportunity to make an individual action that will ultimately have ripple effects. Maintaining a seasonal diet is a simple, delicious way to reduce your carbon footprint, and it feels like you’re indulging.

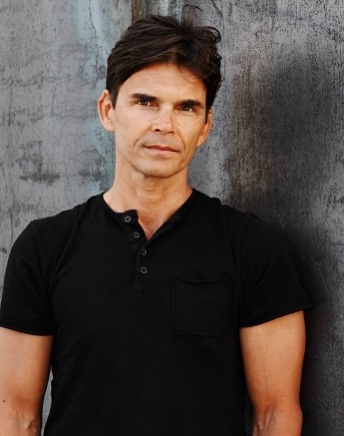

@poweredbymangosChef Matthew Kenney is no stranger to seasonal eating. Growing up on the coast of Maine, he learned how to forage and gather food. The seasons were filled with a new harvest, and Kenney learned to identify which were the best for eating as he was always active and fit and chose to create delicious, healthy dishes from the food he picked himself. When we spoke via Zoom, Chef Kenney stated that making this natural, healthy relationship with food can create a deeper connection with a person and the environment. Part of that relationship is reducing the amount of distance that the food one consumes travels.

While the seasons are inverted on the other side of the hemisphere, making summer fruit available in the winter, the ethics behind moving the food across the sphere are complicated. The amount of distance a piece of fruit or vegetable travels increases the carbon footprint with every meal.

But the environment isn’t the only beneficiary of eating a local, seasonal diet. Chef Kenney also mentioned eating cleaner creates more clarity of mind. It could be because of the reduction of the need for strong preservatives to make the food bloom or because of the lack of nutrition in foods traveling long distances. Fruit and vegetables get shipped off in hopes they will be ripe by the time it gets to its destination. As a consequence, the food lack nutrients and vitamins and even flavor.

@matthewkenneycuisine

Matthew Kenney believes that with enough creativity, any food can be made to taste good. In his plant-based restaurants throughout the globe, he shows this to be true by fusing flavor with nutrition.

As a special for CADA readers, he’s delighted us with one of his recipes you can make at home:

Recipe – BUTTERNUT CARPACCIO

BUTTERNUT CARPACCIO:

1 pound butternut squash

1 teaspoon extra-virgin olive oil

8 sprigs lemon thyme

1⁄2 teaspoon sea salt

QUINCE PURÉE

1 cup quince, peeled and chopped

2 slices/shaves of lemon peel

1 vanilla pod, split 12 sprigs of lemon thyme, wrapped and tied in cheesecloth

1 cup cane sugar

PICKLED MUSTARD SEEDS

1⁄2 cup brown mustard seeds, whole

1⁄2 cup yellow mustard seeds, whole

1⁄2 cup apple cider vinegar 1⁄2 cup agave

1⁄2 cup water, filtered

1 tablespoon sea salt

CANDIED PEPITAS

1 1⁄4 cups pumpkin seeds

1⁄2 cup filtered water

1 cup organic cane sugar

1⁄2 cup maple syrup

1⁄2 teaspoon baking soda

2 teaspoons coconut oil, melted

1 pinch salt

1 pinch cayenne pepper

@mathewkenney

APPLE

1 Granny Smith apple, peeled, small dice

1⁄2 teaspoon lemon juice

1 pinch sea salt

KUMQUAT

2–3 kumquats, seeded and sliced

1 small Chioggia beet, thinly sliced on a mandoline

DEHYDRATED OLIVES

1⁄4 cup black cured olives

Herbs (chervil and mint recommended)

Oxalis

Coriander flowers

Flake salt

DIRECTIONS

Cut the squash right above the bulb where the seeds are stored and reserve the round bottom for another use (not used in this recipe). Peel the squash with a peeler and slice into rounds, using a very sharp mandoline slicer. Toss the squash with olive oil, thyme, and sea salt. Arrange squash rounds into round flower shapes and place them in between parchment paper. Store them on a flat sheet pan in the refrig- erator until ready to serve.

QUINCE PURÉE

Place quince and the remaining ingredients, except the cane sugar, in a saucepan and fill with water, just enough to cover the ingredients. Bring to a boil and simmer for 25 minutes. Re- move from heat and strain. Discard all ingredients except the quince and lemon peel. In a high-speed blender, purée the quince and lemon. Place the cane sugar and quince purée in a saucepan and cook on low for 1 hour.

PICKLED MUSTARD SEEDS

Mix all ingredients in a bowl. Let sit for about an hour to allow the mustard seeds to bloom. Remove half the mixture, blend in a high-speed blender, then pour the blended mixture back into the remaining mixture. Stir. Let the mixture sit out at room temperature 1–2 days.

CANDIED PEPITAS

Toast the pumpkin seeds over medium heat in a pan, con- stantly moving the seeds around the pan so they do not burn. Remove from the heat as soon as they begin to brown around the edges. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper. Attach a candy thermometer to the side of a medium saucepan. To ensure an accurate temperature reading, make sure the candy thermometer does not touch the bottom of the pan. Heat the water, cane sugar, and maple syrup over medium-high heat. Remember to stir constantly with a wooden spoon until the liquid starts to boil. Stop stirring, increase the heat slightly, and allow the mixture to boil until it reaches 285°F. At this point, add the pumpkin seeds to the saucepan and stir continuously, making sure the mixture does not stick to the bottom of the pan until the temperature reaches 300°F. Remove from the heat and stir in the remaining ingredients. The baking soda will cause the mixture to bubble slightly. This is expected.

Working quickly before the liquid begins to harden, pour the mixture onto the parchment-lined baking sheet. Use the back of a wooden spoon to spread the batter evenly across the sheet. Allow the brittle to completely harden at room temperature, about 2 hours. Break the cooled candied pepitas into shards and store in an airtight container at room temperature up to 1 week.

APPLE

Combine the apple with the lemon juice and salt. Set aside.

DEHYDRATED OLIVES

Dehydrate at 155°F in a dehydrator or an oven for 12 hours, or until completely dry. Transfer the dehydrated olives to a food processor and pulse a few times until they are roughly chopped.

FINAL ASSEMBLY

Remove squash rounds from parchment paper and place it on a large round plate. Spoon five 1⁄4 teaspoons of quince purée on top of the carpaccio, followed by five 1⁄4 teaspoons of pickled mustard seeds. Sprinkle 1 tablespoon candied pepitas, 1 tablespoon of diced apples, and 1⁄2 tablespoon dehydrated olives on top. Place thinly sliced kumquats and beets on top. Garnish with chervil, mint, oxalis, coriander flowers, and flake salt.

https://www.foodfutureinstitute.com/

Enter CADA x Food Future Institute Giveaway

If you want to learn how to cook your seasonal food like Matthew Kenney, keep reading…

FFI encourages students to explore their passion for plant-based cuisine founded on technical culinary practices and individual creativity. FFI’s Foundation: Phase I Culinary Program features over 100 lessons outfitted with extensive visual features, including videography, photography and infographics, as well as a curriculum of original recipes designed specifically for this course. Follow the steps below for the chance to win a complimentary enrollment to the Food Future Institute (estimated value of $350).

Steps*:

- Sign up for our newsletter below

- Tag 2+ friends on @cada_culture IG giveaway post

- Follow @cada_consult and @cada_culture

*Terms & conditions apply. Once conditions are met, it’s the luck of the draw if you’re chosen. Winner will be announced Friday afternoon on Nov 20th!

This article is for informational purposes only, even if and regardless of whether it features the advice of physicians and medical practitioners. This article is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment and should never be relied upon for specific medical advice. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of CADA.